The Gregorian Calendar: A Millennial Correction and its Continuing Legacy

Related Articles: The Gregorian Calendar: A Millennial Correction and its Continuing Legacy

Introduction

With enthusiasm, let’s navigate through the intriguing topic related to The Gregorian Calendar: A Millennial Correction and its Continuing Legacy. Let’s weave interesting information and offer fresh perspectives to the readers.

Table of Content

The Gregorian Calendar: A Millennial Correction and its Continuing Legacy

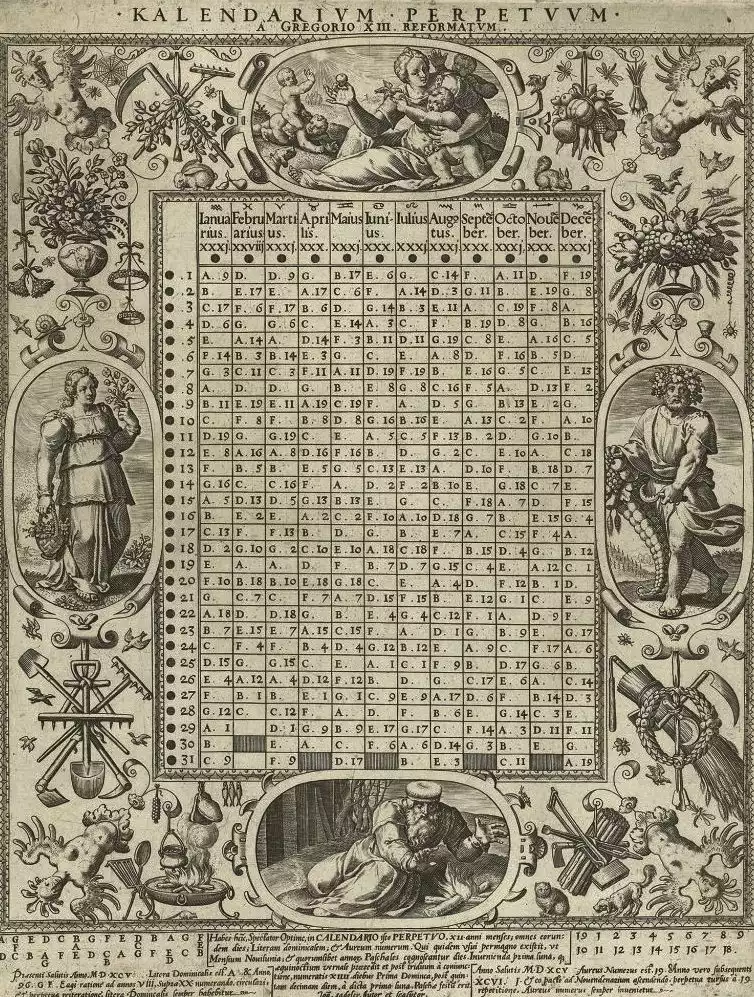

The Gregorian calendar, the internationally accepted standard for civil timekeeping, is a familiar presence in our daily lives. We mark birthdays, holidays, and significant events according to its structure, yet few pause to consider its complex history and the intellectual struggle that birthed it. Its creation wasn’t a simple act of calendrical engineering; it was a complex political and religious undertaking, driven by the need to reconcile astronomical observations with the evolving needs of a burgeoning globalized world. Understanding its origins requires delving into the centuries-long evolution of calendar systems and the specific challenges that led Pope Gregory XIII to decree its adoption in 1582.

Before the Gregorian calendar, the Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BCE, reigned supreme in the Western world. The Julian calendar represented a significant advancement over its predecessors, introducing a standardized 365-day year with a leap year every four years to account for the Earth’s slightly longer orbital period. This leap year addition, while a considerable improvement, overestimated the solar year’s length by approximately 11 minutes and 14 seconds. This seemingly small discrepancy accumulated over centuries, leading to a gradual drift between the calendar and the actual astronomical seasons.

By the 16th century, this drift had become substantial. The vernal equinox, the astronomical marker of the beginning of spring, which traditionally fell on March 21st, had drifted to March 11th. This discrepancy posed significant problems for the Catholic Church, whose liturgical calendar was intricately tied to the astronomical seasons. The date of Easter, for example, was calculated based on the vernal equinox and the full moon, making the drift a matter of theological as well as astronomical concern. The misalignment threatened the accuracy of church observances and created confusion amongst the faithful.

The issue of calendar reform wasn’t new. Various attempts had been made throughout history to refine calendar systems, reflecting a continuous human effort to accurately track the passage of time. However, the 16th century saw a confluence of factors that finally propelled the issue to the forefront. The burgeoning scientific revolution provided the tools and knowledge to refine astronomical calculations with greater accuracy. The invention of the printing press facilitated the widespread dissemination of scientific ideas and proposals for calendar reform. And finally, the centralized authority of the Catholic Church provided the necessary political will to implement a significant change on a global scale.

Pope Gregory XIII, a strong proponent of scientific advancements, commissioned a group of experts, including astronomers and mathematicians, to investigate the problem. This commission, which included Christopher Clavius, a prominent Jesuit astronomer, spent years studying the issue, meticulously analyzing astronomical data and proposing various solutions. Their work culminated in a papal bull, Inter gravissimas, issued on February 24, 1582, which officially introduced the Gregorian calendar.

The key change implemented by the Gregorian calendar was a refinement of the leap year rule. Instead of a leap year every four years, the Gregorian calendar omitted leap years in century years that were not divisible by 400. This subtle adjustment, eliminating three leap days every four centuries, significantly reduced the accumulated error. The change brought the calendar into much closer alignment with the solar year, minimizing the drift for centuries to come.

The implementation of the Gregorian calendar, however, wasn’t without its challenges. The immediate shift required a significant adjustment to the existing Julian calendar. To correct for the accumulated error, October 4, 1582, was followed immediately by October 15, 1582. Ten days were simply dropped from the calendar, a drastic measure that caused considerable confusion and resistance, particularly in some parts of Europe. The transition wasn’t universally adopted immediately; many countries resisted the change, clinging to the Julian calendar for decades or even centuries.

The adoption of the Gregorian calendar wasn’t solely a matter of scientific accuracy; it was also a demonstration of the Catholic Church’s authority and influence. The Pope’s decree, while based on scientific evidence, was ultimately a religious edict, highlighting the Church’s role in setting global standards for timekeeping. This aspect of the calendar’s adoption contributed to its complex and multifaceted legacy.

Over time, the Gregorian calendar gained widespread acceptance, becoming the standard for civil timekeeping across much of the world. Its adoption, however, was a gradual process, reflecting the diverse political and cultural landscapes of different nations. Some countries adopted it relatively quickly, while others resisted for extended periods, leading to variations in calendar usage across regions for centuries. Even today, a few isolated communities still adhere to variations of the Julian calendar.

The Gregorian calendar’s enduring success lies in its remarkable accuracy. While not perfectly aligned with the solar year (a discrepancy of approximately 26 seconds remains), its refined leap year rule ensures that the accumulated error remains minimal, requiring only minor adjustments in the distant future. Its widespread adoption reflects its practicality and its ability to serve the needs of a globalized world requiring a consistent and reliable system for measuring time.

In conclusion, the Gregorian calendar’s creation wasn’t a singular event but rather the culmination of centuries of astronomical observation, mathematical calculation, and political maneuvering. Its adoption in 1582 marked a pivotal moment in the history of timekeeping, reflecting the confluence of scientific advancement, religious authority, and the growing need for a unified global calendar. Its continuing legacy underscores its success in providing a remarkably accurate and widely accepted system for organizing our lives and understanding the passage of time. The seemingly simple act of turning a calendar page each day belies the rich and complex history behind the system that governs our perception of time itself.

Closure

Thus, we hope this article has provided valuable insights into The Gregorian Calendar: A Millennial Correction and its Continuing Legacy. We thank you for taking the time to read this article. See you in our next article!