Deciphering Time: A Deep Dive into the Mayan Long Count Calendar

Related Articles: Deciphering Time: A Deep Dive into the Mayan Long Count Calendar

Introduction

With enthusiasm, let’s navigate through the intriguing topic related to Deciphering Time: A Deep Dive into the Mayan Long Count Calendar. Let’s weave interesting information and offer fresh perspectives to the readers.

Table of Content

Deciphering Time: A Deep Dive into the Mayan Long Count Calendar

The Mayan civilization, renowned for its advancements in mathematics, astronomy, and art, left behind a complex and fascinating legacy: the Long Count calendar. Far from a simple prediction of apocalypse, as popular culture often portrays it, the Long Count is a sophisticated system of timekeeping that reveals a profound understanding of cyclical patterns and the cosmos. This article delves into the intricacies of this calendrical system, exploring its structure, significance, and enduring impact on our understanding of Mayan culture and the nature of time itself.

A System of Cycles Within Cycles:

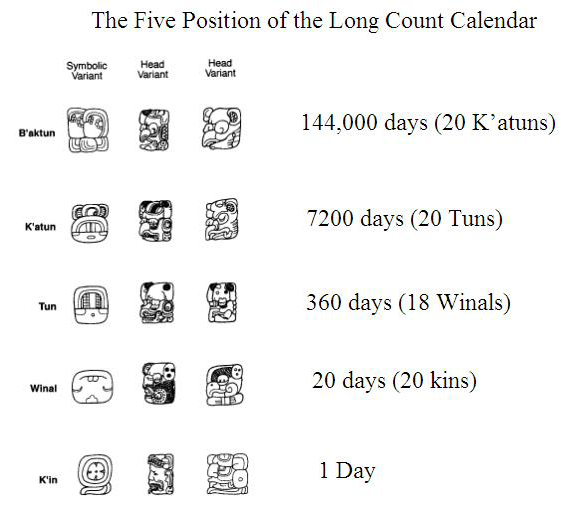

Unlike our Gregorian calendar, which relies on a linear progression of years, the Mayan Long Count operates on a multi-layered system of interlocking cycles. At its core lies a vigesimal (base-20) numerical system, reflecting the Mayan preference for this base, possibly linked to the number of fingers and toes. The Long Count expresses time as a series of units, each a multiple of the preceding one:

- Kin (day): The fundamental unit, representing a single day.

- Uinal (20 kins): A month, consisting of 20 days.

- Tun (18 uinals): A year, comprising 360 days. This reflects the Mayan approximation of the solar year.

- K’atun (20 tuns): A period of approximately 20 years (360 days x 20 = 7200 days).

- B’ak’tun (20 k’atuns): A period of roughly 394 years (7200 days x 20 = 144,000 days). This is a significant unit, representing a major cycle in Mayan cosmology.

Beyond the B’ak’tun, the Long Count continues with further units: the Pictun (20 B’ak’tuns), the Kalabtun (20 Pictuns), and the Alautun (20 Kalabtuns). These larger cycles represent vast stretches of time, far exceeding the scope of recorded human history. The Long Count date is expressed as a series of these units, typically written as B’ak’tun.K’atun.Tun.Uinal.Kin. For example, the date 13.0.0.0.0 marked the end of the 13th B’ak’tun cycle, a date that gained notoriety in the lead-up to December 21, 2012.

Correlation and the Initial Date:

Determining the precise correlation between the Long Count and the Gregorian calendar has been a significant challenge for researchers. The most widely accepted correlation, known as the Goodman-Martinez-Thompson (GMT) correlation, places the initial date of the Long Count at August 11, 3114 BCE. This date, however, is not a creation date of the calendar itself, but rather a reference point, a starting point for measuring time within the system. The actual origins of the Long Count and the Mayan calendar system are likely much older, shrouded in the mists of prehistory. Different correlations exist, but the GMT correlation remains the most commonly used by scholars.

Astronomical Significance and Cyclical Cosmology:

The Mayan understanding of astronomy was remarkable. Their observations of celestial bodies, particularly the sun, moon, and Venus, were extraordinarily accurate. The Long Count calendar wasn’t simply a system for tracking days; it was deeply intertwined with their cosmological beliefs. The cycles within the Long Count reflected the perceived cycles of the cosmos, mirroring the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. The Maya believed in a cyclical universe, where time flowed in repeating patterns, with periods of creation and destruction.

The precise astronomical observations underpinning the calendar suggest a sophisticated understanding of celestial mechanics. The inclusion of a 360-day tun reflects an approximation of the solar year, while other cycles within the calendar correlate with lunar cycles and the synodic period of Venus. These interwoven cycles suggest a holistic view of the cosmos, where the earth and its inhabitants are inextricably linked to the celestial realm.

The End of a B’ak’tun: 13.0.0.0.0 and Misconceptions:

The date 13.0.0.0.0, which fell on December 21, 2012, according to the GMT correlation, was misinterpreted by some as the end of the world or a catastrophic event. This misconception stemmed from a misunderstanding of the Mayan cyclical worldview. The end of a B’ak’tun cycle was not an ending in the linear sense, but rather a completion of one cycle and the beginning of another. It marked a significant transition, a moment of potential renewal and transformation within the larger cosmic cycle.

The Maya themselves did not predict a cataclysm on this date. The prophecies associated with 13.0.0.0.0 were likely more focused on spiritual and cosmological shifts, representing a significant turning point within their cyclical understanding of time. The misinterpretation highlights the danger of imposing linear Western perspectives onto a fundamentally cyclical worldview.

Beyond the Long Count: Other Mayan Calendars:

The Long Count is only one part of the complex Mayan calendrical system. Other calendars, such as the Tzolk’in (260-day sacred calendar) and the Haab (365-day solar calendar), were used concurrently with the Long Count. These calendars interacted in intricate ways, creating a complex system of interlocking cycles that governed various aspects of Mayan life, from religious ceremonies to agricultural practices. Understanding the interplay between these different calendars is crucial for a complete appreciation of the Mayan understanding of time and its significance in their society.

The Enduring Legacy:

The Mayan Long Count calendar stands as a testament to the mathematical and astronomical ingenuity of the Mayan civilization. Its intricate structure and cyclical nature reflect a profound understanding of the cosmos and a worldview fundamentally different from our own linear conception of time. While the 2012 date generated considerable misunderstanding, the calendar itself continues to fascinate and inspire researchers, offering valuable insights into Mayan culture, cosmology, and the human relationship with time. The decipherment of the Long Count is an ongoing process, with new discoveries continually enriching our understanding of this remarkable system and the sophisticated civilization that created it. The study of the Mayan calendar is not just an exploration of a historical system of timekeeping; it is a journey into a different way of perceiving time itself, a cyclical and interconnected universe where the past, present, and future are interwoven in a continuous flow. The legacy of the Mayan Long Count extends far beyond its numerical precision; it is a testament to the human capacity for understanding and representing the complexities of the cosmos.

Closure

Thus, we hope this article has provided valuable insights into Deciphering Time: A Deep Dive into the Mayan Long Count Calendar. We thank you for taking the time to read this article. See you in our next article!