The search for a true scale map of the world is not just a cartographic challenge; it is a mathematical impossibility that has perplexed scientists and geographers for centuries. To understand why, one must first accept a basic geometric truth: you cannot flatten a sphere onto a rectangular plane without distorting it.

Imagine trying to peel an orange in one piece and then pressing that peel perfectly flat against a table. It cannot be done without tearing the skin or stretching it out of shape. This is the exact dilemma cartographers face when projecting the globe onto a piece of paper or a computer screen. Every map is a compromise, trading accuracy in one area for distortion in another.

The Mercator Deception: Why Your Map is Lying

Gerardus Mercator created his famous projection to aid European navigators. Its primary strength was that it preserved angles. If a sailor drew a straight line from point A to point B on a Mercator map, following that compass bearing would actually get them to their destination. For the Age of Exploration, this was a revolutionary tool.

However, the cost of this navigational utility was significant area distortion, particularly as one moves away from the Equator toward the poles. On a standard Mercator map, lines of longitude are parallel vertical lines, whereas on a globe, they converge at the North and South Poles. To keep the lines straight, the map stretches the landmasses horizontally and vertically the further north or south they are.

The most famous example of this distortion is Greenland vs. Africa. On a standard map, Greenland appears to be roughly the same size as Africa. In reality, Africa is approximately 14 times larger than Greenland. Africa covers 30.37 million square kilometers, while Greenland covers only 2.16 million square kilometers.

Similarly, Europe is often depicted as being larger than South America, yet South America is nearly double the size of Europe. Alaska frequently appears as large as Brazil, despite Brazil being five times larger. These distortions have profound psychological effects, subtly reinforcing a worldview that exaggerates the importance and physical dominance of Northern Hemisphere nations.

The Contenders for Accuracy: Equal-Area Projections

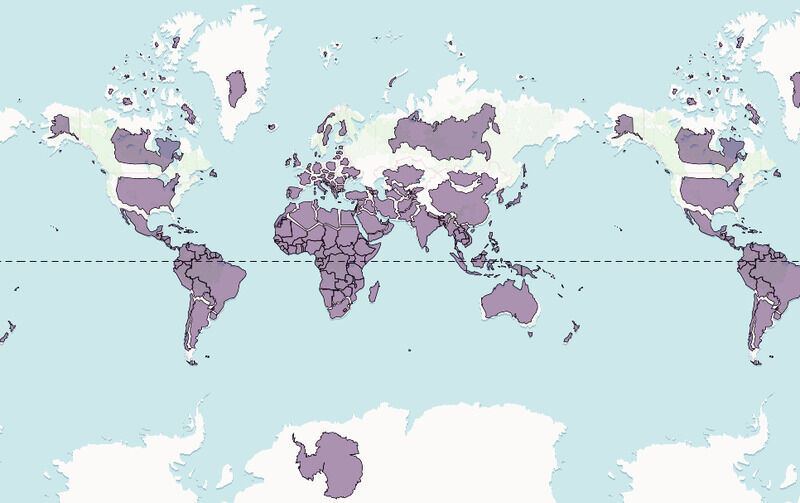

In response to the gross inaccuracies of the Mercator projection, cartographers have developed equal-area projections. These maps prioritize the correct representation of landmass sizes relative to one another, often at the expense of shape or distance accuracy.

The Gall-Peters Projection

Perhaps the most controversial challenger to the Mercator status quo is the Gall-Peters projection. Popularized in the 1970s by Arno Peters, this map sought to correct the ‘imperialist’ bias of the Mercator map by showing the developing world in its true proportion to Europe and North America.

On the Gall-Peters map, Africa dominates the center, correctly shown as a massive continent capable of swallowing the United States, China, India, and most of Europe with room to spare. However, to achieve this area accuracy, the projection stretches landmasses near the equator vertically and squashes those near the poles. The result is a world that looks somewhat melted or ‘droopy,’ which critics argue is aesthetically unpleasing and distorts the shapes of countries beyond recognition.

The Winkel Tripel Projection

Recognizing that neither Mercator nor Gall-Peters offered a perfect solution, the National Geographic Society adopted the Winkel Tripel projection as its standard in 1998. This is a compromise projection. It does not attempt to be perfectly conformal (preserving angles) or perfectly equal-area.

Instead, the Winkel Tripel attempts to minimize the sum of all three main types of distortion: area, direction, and distance. The result is a map that looks more ’rounded’ and offers a balanced view of the world that is arguably the best compromise for general reference maps, even if it isn’t strictly a ‘true scale’ map in every mathematical sense.

The AuthaGraph: The Most Accurate Map to Date?

In 2016, a Japanese architect named Hajime Narukawa won the Good Design Grand Award for the AuthaGraph World Map. This map represents perhaps the closest we have come to a true scale map on a 2D surface that preserves both shape and size with minimal distortion.

Narukawa’s method was inspired by origami. He divided the spherical surface of the Earth into 96 triangles, transferred them onto a tetrahedron (a pyramid shape), and then unfolded that shape into a rectangle. The result is a map where continents are not fragmented, and their relative sizes and shapes are maintained with remarkable accuracy.

Unlike the Mercator, the AuthaGraph does not expand the poles. Antarctica is visible and accurately sized. Unlike the Gall-Peters, the shapes of the continents are not elongated grotesquely. While it effectively rearranges the orientation of the oceans to achieve this continuity, it provides a perspective that many experts agree is the most scientifically accurate representation of our planet on paper.

Why True Scale Matters

Why does it matter if our maps are wrong? Cartography is not just about geography; it is about power and perception. The size of a country on a map correlates subconsciously with its perceived importance. By shrinking the Global South (Africa, South America, Southeast Asia) and enlarging the Global North (Europe, North America, Russia), standard maps have historically marginalized developing nations.

Educational institutions are increasingly moving away from the Mercator projection to teach students a more equitable view of the world. Boston Public Schools, for example, made headlines when they switched to the Gall-Peters projection, sparking discussions among students about perception and reality.

Digital Solutions: The End of Projections?

In the digital age, the quest for a perfect 2D map may become less critical thanks to 3D rendering. In 2018, Google Maps updated its desktop interface to use a Globe Mode. When a user zooms out, the map no longer stays flat; it becomes a sphere.

This shift eliminates the projection problem entirely. By presenting the Earth as a globe, digital tools can show true scale, true direction, and true shape simultaneously. Tools like ‘The True Size Of’ website allow users to drag countries over one another to compare their actual footprints, revealing the shocking disparities hidden by traditional maps.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the flat earth map a true scale map?

No. Maps used by flat earth proponents generally use an Azimuthal Equidistant projection centered on the North Pole. While distances from the center point are accurate, the distortion of shape and area increases massively the further you get from the center. Australia, for example, becomes incredibly wide and distorted on these maps.

Why don’t we just use the AuthaGraph everywhere?

While accurate, the AuthaGraph is unfamiliar. It orients the world in a way that breaks the continuity of the Pacific or Atlantic oceans depending on how it is tiled, and it doesn’t align with the cardinal directions (North is not always ‘Up’) in the simple grid way that the Mercator does. For navigation and general familiarity, the Mercator or Robinson projections remain easier to read.

What is the Tissot’s Indicatrix?

This is a mathematical tool used to visualize distortion. It involves placing circles at regular intervals on a globe and then projecting them onto a map. On a perfect map, all circles would remain circles of the same size. On a Mercator map, the circles grow massive near the poles. On a Gall-Peters map, the circles are squashed into ovals. Tissot’s Indicatrix helps cartographers quantify exactly how ‘wrong’ a map is.

Conclusion

To understand the world at true scale, we must look to equal-area projections like the Gall-Peters, innovative designs like the AuthaGraph, or simply spin a globe. Recognizing that Africa is larger than the USA, China, India, Japan, and all of Europe combined is not just a trivia fact; it is a necessary step in understanding the true geopolitical and physical layout of our planet.